- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

Beneficial Strategies for Architectural Students to Refine Concept

Enhance your architectural project concepts with our expert guide. From embracing design briefs to site analysis, we explore unique strategies to refine design ideas. Discover the game-changing impact of technology, such as virtual reality, CAD, and BIM, in streamlining processes and improving architectural communication.

Table of Contents Show

In the realm of architectural education, the design studio is a vibrant hub of creativity and innovation. It’s where students are encouraged to push boundaries, challenge their beliefs, and explore concepts beyond their existing knowledge. College projects, often seen as daunting tasks, are in fact opportunities for students to flex their design muscles and bring their unique ideas to life.

The journey from a vague brief to a comprehensive design proposition is a transformative one, filled with lessons and discoveries. It’s not just about creating a functional and aesthetically pleasing structure, but also about developing a deep understanding of the spaces we inhabit and the ethical considerations that shape our designs.

So, how do students navigate this complex process and improve their project concepts? Join us as we delve into the heart of architectural education and explore the strategies that can help students refine their designs and truly make their mark in the world of architecture.

Understanding Architectural Concepts

Navigate through the dense fog of architectural education by understanding architectural concepts thoroughly. Begin by recognizing the substantial role concepts play in architectural projects.

The Role of Concepts in Architecture

A central player in architecture projects, the concept serves as the backbone that champions the project forward. Transforming a mere studio project into a successful architectural marvel demands a sturdy concept. Without this crucial component, your project teeters on the edge of relevance. Conversely, anchoring your project in a sound concept not only strengthens its foundation but also propels passion and enthusiasm into the project’s development.

Undeniably, the concept enacts a critical role in decision-making within design. Originating often as an abstract response to a problem analysis, concepts evolve constantly to reflect a deeper understanding of design and site elements. No concept remains static, nor remains confined to a singular type throughout a project. An architect’s toolbox might hold a variety of architectural concepts, each adjusting and developing according to the progression of the design process.

A successful concept carves a narrative, a story of the machinery driving the design. This story, built on your architectural concept, might become the project’s identity, its soul. Despite their abstract nature, concepts combine with elements of design to create clear frameworks for architects and reflect beautifully in the final outcome.

However, attaining this abstract idea, this concept, is not always a walk in the park. Developing an architectural concept often proves a challenging task, tormenting even experienced architects. Yet, despair has no place in architecture; although the path to inspiration is not marked, numerous methods are available to try.

Pre-Design Research and Analysis

Taking the first steps in an architectural venture requires a student to delve into pre-design research and analysis. This initial modal positions students for a smoother execution of their project concepts.

Embracing the Design Brief

As architects-in-the-making, students embrace the design brief, understanding its significance as the kernel of their architectural endeavor. The brief provides an opportunity to think out of the box, challenging the status quo and beating the path to creativity. Trifle not with the brief, for it is in embracing it, students begin the journey to creating masterpieces. Assignments and tasks, such as designing houses, serve not only as learning opportunities—they also challenge belief systems, and push the boundaries of spatial understanding.

Site Analysis and Contextual Study

Plot your path to success through comprehensive site analysis and contextual study, a cornerstone for any design project. A clear and concise analysis of the project’s site and context drives a comprehensive understanding of environmental, socio-cultural, and technological factors. The topography, climate, connectivity, adjacent buildings—all partake in shaping the design’s narrative and identity. Our role? We harness the power of context, turning constraints into opportunities. Guided by a clear understanding of the interplay between design and context, architectural student projects extrapolate from the real world, breaching the borders of imagination and creativity.

Generating and Refining Design Ideas

Following an understanding of the project context, the endeavor of generating and refining design ideas begins, prompting the evolution from vague concepts into intentional architectural solutions.

Functional Approach to Conceptual Design

Embrace a functional approach from the onset of the project. Consider the typology of the building and its proposed use, from a hospital, a museum, a home, or beyond. Gather information about the specific needs of the target users and the challenges they face in the built environment. Explore the required structural system, occupant movement patterns, and signature features attributed to this building type. For instance, a hospital design may address unique aspects like patient privacy, advanced medical equipment accommodation, or seamless emergency access. Embed such insights into the very fabric of your design, ensuring it addresses real-world needs.

Investigating Materiality

Apart from serving a functional requirement, the choice of material contributes significantly to the identity of the design. During the process of conceptualization, explore the expressive potential of various materials in conveying the intended spatial atmosphere. Consider the textural quality, acoustic property, durability, and the aesthetic appeal of each material and how it responds to light and shadows. For example, with brick walls, envision how it creates a robust and rustic appeal, while glass walls may imbue the space with a sense of transparency and lightness.

Exploring Conceptual Themes

This stage involves the extraction of abstract ideas from the gathered data. Reflect on the core values the building should embody or the story it strives to tell. These conceptual themes act as a guiding thread intertwined throughout the design process. For example, with a museum project focused on local history, a potential theme could be the ‘Memory of the Place.’ Such themes could inspire multiple design elements like the spatial layout, form, material usage, and even architectural details.

Analyzing Context and Form

Contextual analysis helps shape the building’s relation with its site and surroundings. Purposefully integrate natural features or cultural landmarks, ensuring the design maintains harmony with its environment. Investigate factors like climatic conditions, topography, key view corridors, and solar orientation that can greatly influence the building form. Similarly, consider how a visitor might approach the building, fostering an intuitive wayfinding experience. Such a comprehensive study of the context enriches the design, contributing to its sense of place and belonging.

Enhancing Creativity in Concept Development

Diving into the methodology of conceptual elaboration, we’ll explore a variety of critical strategies that help architectural students enhance their creative muscles.

Ideation Techniques for Architectural Students

A plethora of ideation techniques exist, equipping architectural students with the tools to generate innovative ideas. Brainstorming serves as an excellent start, enabling the generation of a large quantity of ideas in a short duration. Another useful technique involves the examination of analogous fields or scenarios – think of how a biological ecosystem functions, for instance, and drawing parallels to architectural systems. This method can often bear unexpected and creative design solutions. Yet another strategy involves challenging norms or preconceived ideas, much like the philosophy advocated by architectural educational programs.

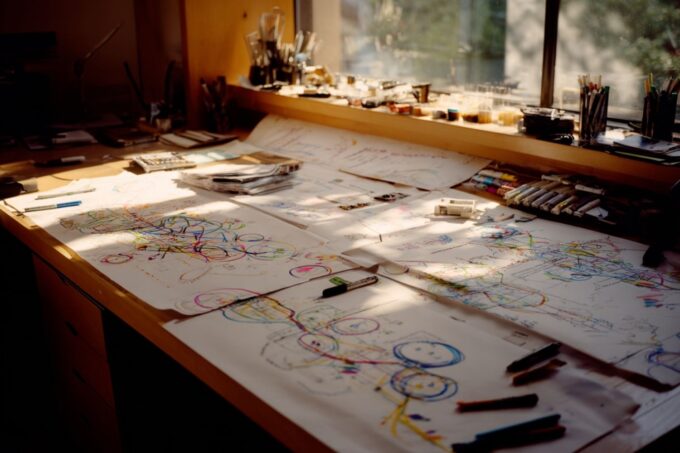

Sketching to Visualize Concepts

Often, one can untangle notions visually better than verbally. To furnish a potent tool in this aspect, sketching assumes a pivotal role in the conceptualization phase, offering a direct line from the mind to the paper. Quick sketches allow for a rapid exploration of ideas, helping students understand their topography better. This familiarity then leads to efficient and effective conceptual iterations. Additionally, varying sketching styles – from loose gestural illustrations to precise and methodical drawing – can stimulate different kinds of design thinking.

Breakdown of Complex Problems

The strategic breakdown of complex problems can drastically simplify the design process. Assessing the overall architectural challenge and breaking it into smaller pieces can make the task appear much less daunting. Each piece becomes a puzzle, requiring its unique solution. Not only does this method offer control over intricate design problems but it also provides diverse perspectives on the project, encouraging innovation.

Mind Mapping for Thematic Development

Mind mapping serves as an instrumental process to develop thematic concepts. It begins with a central idea and then radiates outwards, incorporating interconnected thoughts and themes. This method lends a fantastic platform to visually organize your concepts and ideas. It helps create a hierarchy of information, making it easier for students to understand and communicate their design premises. Furthermore, mind mapping can also assist in making associations between different aspects of the design, leading to a cohesive and comprehensive architectural concept.

Design Iteration and Evolution

In the inherently dynamic field of architectural design, continuous adaptation and thoughtful iteration directly influence the maturity and relevance of design concepts.

The Importance of Critique and Revision

Critique and revision play pivotal roles in architecture. A robust internal critique leads to the identification of weak design elements and helps evolve our projects. Dedicate sufficient time for examining your design proposals from various perspectives, such as functionality, aesthetics, sustainability, and user experience. Exploring these different viewpoints can expose hidden issues and inspire amendments promoting project improvement. For instance, critiquing a residential design from an environmental sustainability perspective might reveal the use of non-eco-friendly materials or design choices negatively impacting energy efficiency.

Adapting to New Information and Challenges

The architecture projects we tackle demand a high degree of adaptability and resilience. Sketching out a design concept is just the beginning. As the design process unfolds, it often brings new information, unexpected site conditions, or user feedback that challenge our first design ideas. Embrace this dynamic nature of architecture and view these challenges as opportunities to refine your designs and acquire valuable problem-solving skills. For instance, discovering a groundwater issue on a building site could lead you to incorporate sustainable water management features into your design, transforming a potential setback into a standout project feature.

Leveraging Technology for Concept Improvement

Incorporating advanced technology proves instrumental in enhancing concept improvement efforts in the field of architecture. Shaping diverse concepts and elevating communication of these concepts becomes accessible through the utilization of digital tools and advanced technologies like virtual reality or 3D modeling.

Digital Tools for Conceptualization and Design

Harnessing the power of digital tools promotes efficient conceptualization and design in architecture. Tools such as Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software streamline the creation, modification, analysis, or optimization of a design, therefore facilitating immediate realization of ideas on a virtual platform. Notably, Building Information Modeling (BIM) technology empowers architects to construct detailed 3D models of their designs, providing a comprehensive view of the project that enables an enhanced understanding of spatial relations and material considerations.

For instance, investing in a high-performance computer strengthens everyday work and prevents potential inconveniences like software not responding or irreversible errors. Consequently, it fosters an environment where architects can seamlessly express their creative ideas and design concepts, ultimately elevating the quality of their projects.

Virtual Reality and 3D Modeling in Presentations

Integrating Virtual Reality (VR) and 3D modeling technologies in the presentation stage of architectural projects offers a transformative experience. It deepens stakeholders’ immersion, providing them with an engaging, comprehensive understanding of the architectural space right before actual construction commences.

Firstly, VR grants an interactive exploration of designs, enabling architects and clients to virtually venture through the proposed building’s spaces. It gives a feel of the building’s size, spatial arrangements, and even the interplay of light and shadow within the premises. This immersive experience empowers architects to glean valuable insights that assist in the iterative refinement of their designs.

Secondly, the incorporation of 3D modeling in presentations improves clarity and the overall understanding of designs. Detailed 3D models, potentially coupled with video walkthroughs depending on the architect’s skill level, successfully depict spatial relationships based on program, interpretation of functions, and the value of use. Such illustrations equip stakeholders with in-depth understanding, thereby fostering informed decisions, mitigating miscommunications, and encouraging fruitful, collaborative discussions.

Conclusion

Architectural design projects thrive on enhancing concept development. Success in the field hinges heavily on the ability to refine project concepts, a process primarily enabled by a combination of strategy, practice, and technology.

- Optimize Research Techniques: Comprehensive research shapes the foundation of effective architectural concepts. Research can incorporate studying the works of pioneering architects, analyzing innovative buildings or designs, and exploring different architectural styles and philosophies. It is indispensable in maintaining abreast with the latest trends, advancements, and shifts in the architectural landscape.

- Critique the Design Proposition: Constructive critique provides a robust feedback loop essential for refining project concepts. It provides opportunities to evaluate design parameters such as functionality, aesthetics, sustainability, and user experience, and uncover potential areas of improvement. For instance, in group design reviews, insights and suggestions might improve the conceptual understanding and design.

- Iterative Design Modeling: Adopting an iterative process, whether it’s sketching over previous designs or diagramming concepts alongside each other, pushes the boundaries of design possibilities. It assists in revealing newer trajectories, discarding redundant elements, and refining the project towards a more evolved design.

- Technological Integration: Today’s technology offers architects a plethora of tools to draft, visualize, analyze, and refine architectural concept designs. Applications such as CAD and BIM software, virtual reality, and 3D modeling help streamline design processes, provide in-depth project analysis, and simplify communication within teams, improving the overall quality of the architectural project.

- Continuous Learning: Lastly, fostering a culture of continuous learning and adaptation permits designers to remain innovative and responsive to an ever-changing environment. It could involve participating in design workshops, attending architectural seminars, engaging in design competitions, or simply reading quality architectural literature. In this way, designers enhance their knowledge reservoir and can offer fresh perspectives to project refinements.

Understanding these procedural elements not only empowers students in their academic journeys but also equips them with the necessary skills and attitudes towards continued personal and professional development in architecture.

Submit your architectural projects

Follow these steps for submission your project. Submission FormLatest Posts

How to Study Ancient Architecture: Tips and Resource

A practical guide to studying ancient architecture across Egyptian, Greek, and Roman...

10 Common HVAC Mistakes in Architecture to Avoid

Learn the most common HVAC mistakes in architectural design and how to...

8 Tips for Designing a Productive Garden Studio

Transform your outdoor space into a productive sanctuary. Learn essential design principles...

7 Tips for Designing a Kid-Friendly Creative Corner

Learn how to design the perfect kid-friendly creative corner with these 7...

Leave a comment