- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

Table of Contents Show

Buildings are not mere static structures. They interact with their surroundings in ways that significantly influence both the environment and the experiences of those who occupy or pass by them. Understanding the spatial relations of buildings is crucial for architects, urban planners, and environmentalists alike, as it can dictate the success and sustainability of a structure within its environment.

Light Interactions

One of the most observable ways buildings interact with their environment is through light. Buildings can either maximize or minimize natural light, influencing not only the ambiance within but also the surrounding spaces. The design of fenestration, orientation, and use of reflective materials can bring about variations in shading, light penetration, and even light pollution in urban areas.

Wind and Airflow Patterns

Tall structures, especially skyscrapers, can significantly alter wind patterns in urban environments. These can create wind tunnels on streets, making them uncomfortable or even hazardous for pedestrians. However, when designed thoughtfully, buildings can harness these winds for natural ventilation, reducing the need for artificial cooling.

Thermal Impact

The choice of building materials and design can affect the thermal performance of a building. For instance, buildings with green roofs or facades can reduce the urban heat island effect, cooling their immediate surroundings. Conversely, dark surfaces can absorb and re-radiate heat, raising temperatures in the vicinity.

Rainwater Management

How a building is designed can influence how rainwater is directed, absorbed, or drained. Roofs that allow rainwater harvesting or permeable pavements can prevent rapid runoff, decreasing the chances of urban flooding and facilitating groundwater recharge.

Green Spaces and Landscaping

The integration of vegetation into and around buildings can influence local biodiversity, air quality, and even the psychological well-being of inhabitants. Trees, shrubs, and gardens can act as buffers, reducing noise pollution, providing shade, and serving as habitats for various species.

Cultural and Social Interactions

Buildings can shape social interactions and influence cultural norms. A building’s spatial relationship with its surroundings can encourage or discourage public gatherings. Squares, courtyards, and open spaces can act as community hubs, fostering social interactions.

Transportation and Movement

The positioning of buildings in relation to transportation hubs, roads, and pathways can dictate the flow of people and vehicles. This not only impacts traffic patterns but also determines how accessible a building is to its users.

Economic Impacts

From an economic perspective, the spatial positioning of commercial buildings in relation to others can affect business success. Proximity to transport links, visibility from main roads, and the ease of access can influence customer footfall and commercial viability.

The spatial relationship of buildings with their environment goes beyond aesthetics. It plays a vital role in shaping the environmental, social, and economic fabric of our cities. As we continue to grapple with urbanization and its associated challenges, a deeper understanding of these spatial interactions is essential in creating sustainable, harmonious, and resilient urban landscapes.

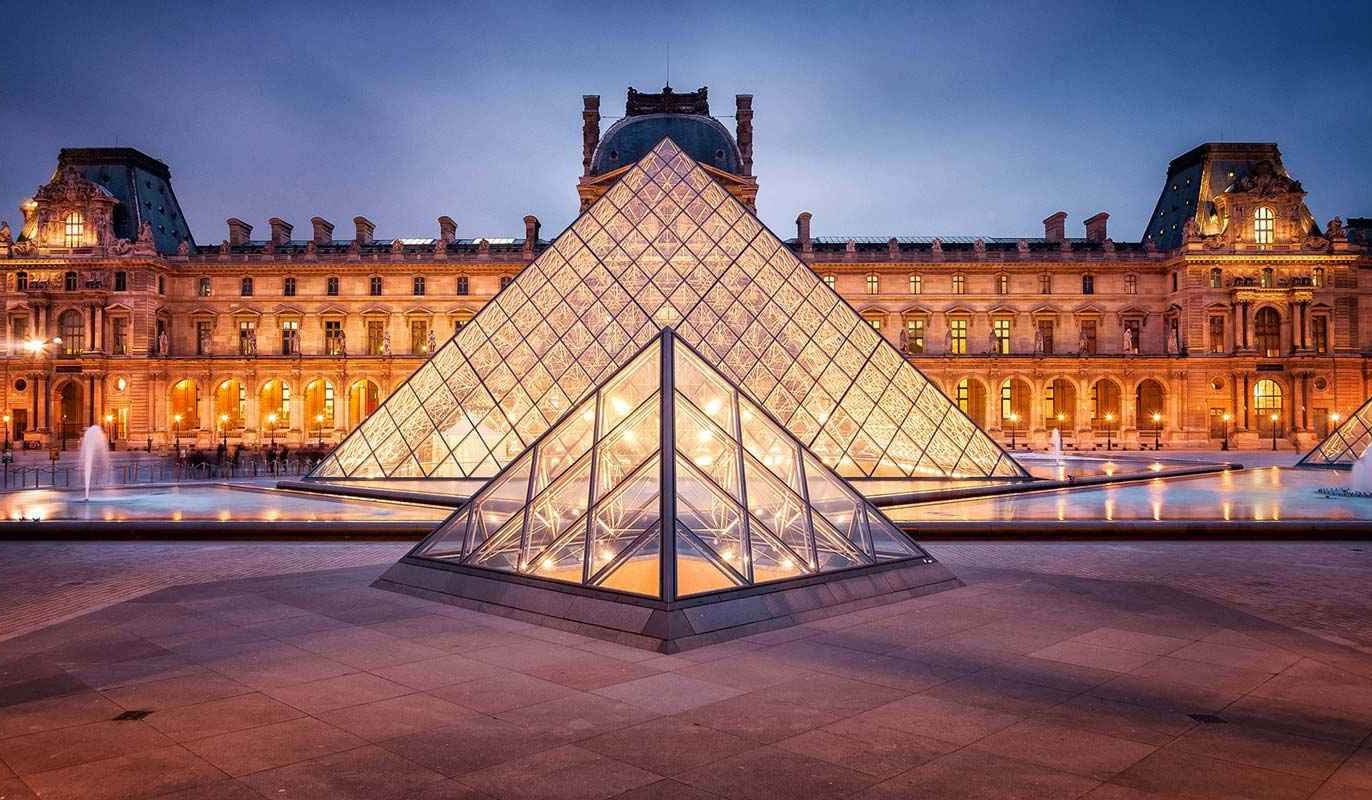

- Light Interactions: The Louvre Pyramid, Paris Designed by I. M. Pei, this glass and metal pyramid is a study in optimizing light. Acting as the main entrance to the museum, the pyramid allows natural daylight to flood the lobby below, creating a unique ambiance and reducing the need for artificial lighting during the day.

Credit: The Louvre Pyramid, Paris | Architect: I. M. Pei Built in: 1… | Flickr - Wind and Airflow Patterns: The Gherkin (30 St Mary Axe), London This iconic skyscraper has a unique aerodynamic shape. Its spiraled design helps divert winds around the building, preventing the creation of strong wind tunnels at the street level, which can be a common problem with tall buildings in dense urban areas.

- Thermal Impact: BedZED (Beddington Zero Energy Development), London This eco-village was designed with sustainability at its core. Its design optimizes passive solar heating, using high insulation and thermal mass to maintain consistent internal temperatures, reducing the need for artificial heating and cooling.

Credit: BedZED – the UK’s first major zero-carbon community – Bioregional - Cultural and Social Interactions: La Plaza Cultural, New York City This community garden in the Lower East Side serves as a hub for social and cultural gatherings. Its design, which invites people in, and its programming, ranging from film screenings to gardening workshops, make it a focal point of community interaction.

Credit: Portland City Hall (Oregon) – Wikipedia - Rainwater Management: Portland City Hall, Oregon Portland has been at the forefront of green design in the U.S. Their city hall incorporates a green roof that captures and manages rainwater, reducing the burden on the city’s stormwater system and mitigating the heat island effect.

Submit your architectural projects

Follow these steps for submission your project. Submission FormLatest Posts

Making Every Inch Count: Smart Solutions for Warehouse Storage

Table of Contents Show Think Vertical, Not Just HorizontalGetting Smart About Storage...

DIY Shed Building: 5 Costly Mistakes That’ll Make You Want to Cry (And How to Skip Them)

Table of Contents Show Mistake 1: Skipping the Foundation Prep (Because Who...

10 Frank Gehry Buildings You Need to See Before You Die

A curated guide to ten of the most significant Frank Gehry buildings...

High-Value Interior Design Strategies That Will Turn Your Property from Ordinary to Extraordinary

Table of Contents Show Strategic Space ArrangementLeveraging the Impact of Color ChoicesPlanning...

Leave a comment