- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

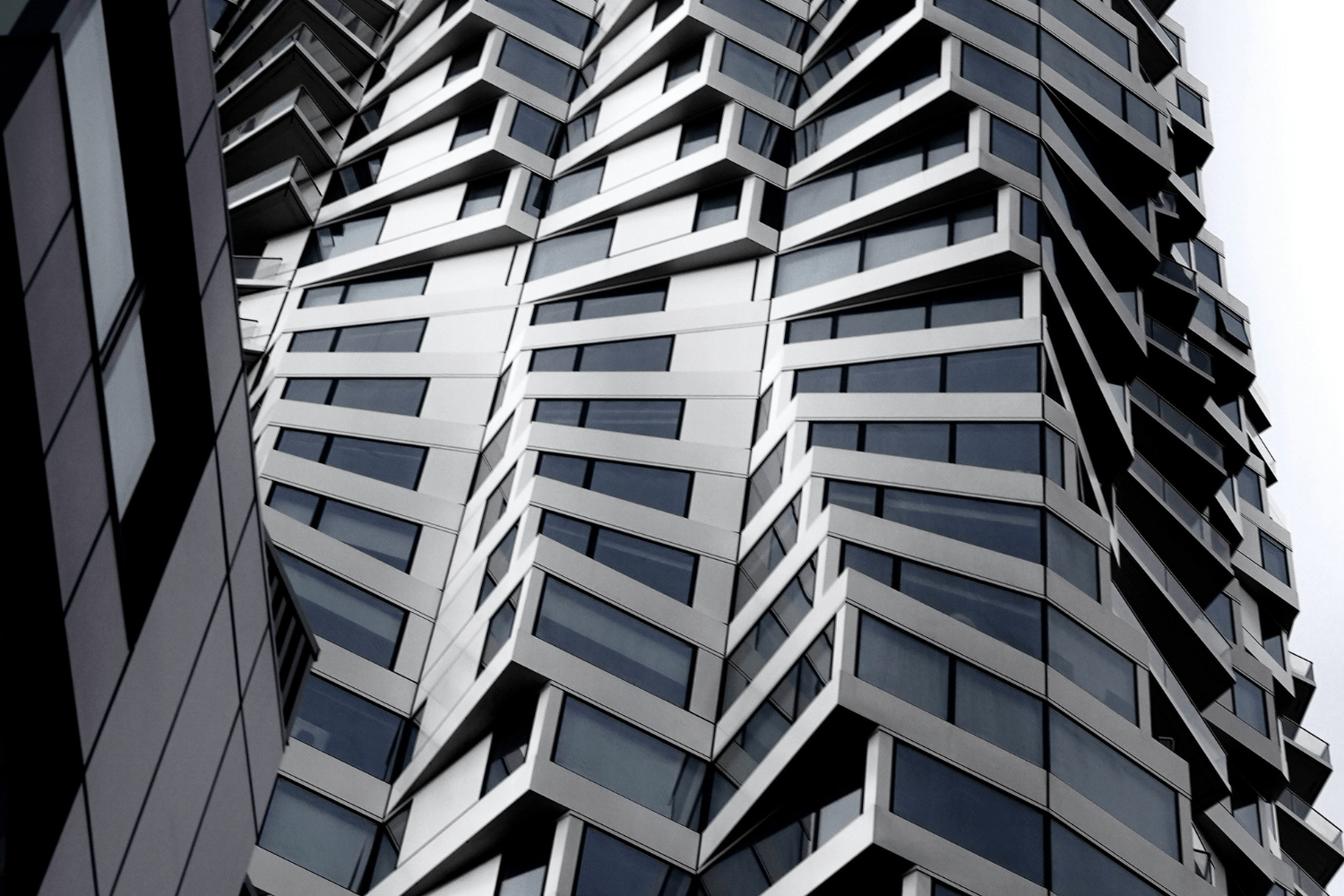

Brutalism Revisited: Raw Concrete Still Divides Opinions

Brutalism revisited: Raw concrete still stirs debate. This article traces béton brut from Le Corbusier to the Smithsons, weighing its postwar optimism against maintenance woes and maligned cityscapes. Explore preservation and adaptive reuse that honor its craft while shaping humane, community-first design.

Table of Contents Show

Brutalism revisited: raw concrete still divides opinions. We can feel that split whenever we walk past a hulking civic building or a once-maligned housing estate now finding new fans on Instagram. Some of us see courage and clarity: others, coldness and scale run amok. In this piece, we unpack what the movement actually stood for, why it fell from grace, and how its bones are being revalued in a low‑carbon, retrofit-first era.

What Brutalism Is—And Isn’t

Origins And Etymology

We often trace brutalism to the mid‑20th century, with roots in Le Corbusier‘s béton brut, literally “raw concrete.” The phrase morphed into “Brutalism,” championed by Alison and Peter Smithson in the 1950s as an ethic of truth to materials and legible structure. It wasn’t about violence or hostility: it was about toughness and candor. From the Barbican in London to Boston City Hall, architects favored exposed structure, repetitive modules, and a social agenda that prioritized collective spaces.

Material Honesty And Monumentality

At its best, Brutalism is a manifesto of material honesty: we read the pour lines, the formwork grain, the way light breaks across a ribbed facade. There’s monumentality, yes, but also surprising nuance, the chamfers, board‑marked textures, and carefully splayed stair towers. What it isn’t: a monolith of “ugly concrete.” Many brutalist works are precisely detailed, deeply crafted, and situationally responsive, even when they wear their mass with pride.

From Postwar Promise To Public Backlash

Social Housing And Civic Ambitions

We can’t separate Brutalism from postwar optimism. Governments urgently needed housing, schools, and civic centers. Concrete offered speed, economy, and fire resistance, and the megastructure promised shared amenities, elevated walkways, communal gardens, the works. Estates like Park Hill in Sheffield embodied this hope: “streets in the sky” intended to preserve community ties while rehousing thousands.

Maintenance, Weathering, And Missteps

Promises met reality. Concrete carbonates and spalls if detailing and maintenance lag. Water tracking, poor drainage, and thin cover to rebar left many buildings streaked and crumbling. Cost‑cutting, system‑built panels, and indifferent management compounded the issue. High‑profile failures, amplified by images like the 1972 demolition of Pruitt‑Igoe in St. Louis, hardened a narrative that equated raw concrete with social failure, even where the root causes were policy and upkeep, not just design.

The Case Against: Alienation, Scale, And Urban Failures

Human Scale And The Public Realm

Critics argue that some brutalist ensembles ignored human scale. Windswept plazas, blank podiums, and overly deep plans can deaden street life. When retail shutters or community services move out, the megastructure becomes inert, hard to cross, harder to love. We’ve learned that active edges, mixed uses, and fine‑grained entrances matter as much as structural bravado.

Crime, Stigma, And Media Narratives

From the 1970s onward, tabloid shorthand made concrete the visual stand‑in for crime and neglect. Oscar Newman’s “defensible space” and later CPTED principles reshaped how we think about surveillance and access. But we should be honest: social stressors, underfunding, and policy churn did more damage than any board‑marked column. The stigma stuck anyway, cementing the idea that “brutalism revisited raw concrete still divides opinions” for a reason.

The Case For: Craft, Clarity, And Cultural Value

Concrete As Craft: Formwork, Joints, And Texture

When we look closely, the craft is undeniable. Good brutalist concrete is a record of making, tie‑hole patterns, shutter marks, crisp arrises that catch the sun. Architects coordinated lifts, joint locations, and aggregates like a score of music. Even the most muscular buildings reveal refinement in stair details, soffit ribs, and the choreography of light and shadow.

Iconic Works And Everyday Brutes

Think of the Barbican Estate’s layered public spaces, or Boston City Hall’s expressive civic rooms read on the facade. Marcel Breuer’s museums, Lina Bo Bardi’s SESC Pompéia, and Habitat ’67’s stack of prefabricated modules show the movement’s range. And the “everyday brutes”, libraries, churches, parking structures, anchor local memory. Once we strip away grime and suspicion, many communities rediscover pride in these concrete landmarks.

Revival, Preservation, And Adaptive Reuse

Conservation Techniques For Concrete

Preservation isn’t glamorous, but it’s effective. We’re seeing carbonation‑induced corrosion addressed with patch repairs, re‑alkalization, and, where needed, cathodic protection. Hydrophobic impregnations and breathable mineral coatings reduce water ingress without smothering the surface. Crucially, details, drip edges, flashings, proper cover, get corrected so repairs last. Conservation today is less about hiding concrete than helping it age with grace.

Reprogramming And Retrofit Success Stories

Adaptive reuse has rewritten public perception. Park Hill’s phased retrofit by Urban Splash and collaborators retained structure while adding mixed uses, better insulation, and lively ground floors. The former Whitney (Breuer Building) found new life as the Met Breuer and then Frick Madison, proving that robust frames can flex to new curatorial needs. University libraries, town halls, and theaters across Europe and North America are being upgraded with efficient systems, seismic reinforcement, and improved access, evidence that the greenest building is often the one we already have.

Lessons For Contemporary Design

Balancing Boldness With Belonging

We can keep the courage, clear structure, honest materials, while remembering that people experience buildings at five miles per hour. That means active edges, sunlight, planting, and tactility at hand height. Bold forms shouldn’t come at the expense of wayfinding or everyday joy.

Carbon, Retrofit, And Material Futures

Concrete’s carbon footprint is the elephant in the room. The path forward blends retrofit‑first thinking with lower‑carbon mixes (GGBS, fly ash, LC3), improved curing, and performance‑based specs that avoid over‑design. We should add bio‑based finishes where sensible, design for disassembly, and count whole‑life carbon. If Brutalism taught us to be honest, let’s be honest about emissions, and the massive carbon savings in reusing existing frames.

Conclusion

We don’t need to pick a side so much as learn from the split. Brutalism’s clarity, durability, and social ambition still inspire: its mistakes around scale and maintenance warn us where not to tread. As we upgrade and reuse these concrete giants, we can move past caricature. Brutalism revisited: raw concrete still divides opinions, but it also invites us to build bravely, and belong better.

- architectural opinions on brutalism

- architecture style debates

- brutalism architecture revival

- brutalism vs modernism

- brutalist design inspiration

- Brutalist interior design

- concrete building aesthetics

- concrete construction techniques

- controversial building designs

- Famous Brutalist buildings

- history of brutalist architecture

- iconic concrete structures

- industrial style architecture

- mid-century modern architecture

- modern brutalism

- modernist concrete buildings

- raw concrete design

- raw concrete finishes

- raw materials in architecture

- urban brutalism

Submit your architectural projects

Follow these steps for submission your project. Submission FormLatest Posts

How Facades Tell Cultural Stories

How facades tell cultural stories—decode symbols, materials, and climate cues with regional...

Top 10 Examples of Dynamic Facade Designs Around the World

Dynamic facades are transforming contemporary architecture with systems that move, react, and...

8 Trends in Dynamic Facade Design You Need to Know

Dynamic façades are reshaping contemporary architecture by responding to climate, light, and...

Transform Ordinary Facades Into Striking Designs With These Key Upgrades

Table of Contents Show Refreshing the Color SchemeUpgrading Windows and DoorsEnhancing Architectural...

Leave a comment