- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

How Upcycling Materials Is Redefining the Future of Architectural Construction

Upcycling materials is reshaping how architecture understands value, time, and responsibility. Rather than treating waste as an endpoint, contemporary design reframes existing materials as active resources that carry cultural memory, embodied energy, and spatial potential. This shift signals a deeper transformation in construction culture—one rooted in continuity, circular thinking, and architectural intelligence.

Table of Contents Show

Architecture has always been a material practice before it is a formal one. Long before buildings are read as icons, they exist as assemblies of matter—extracted, processed, transported, and fixed into place. In the contemporary moment, this material reality has become impossible to ignore. Climate breakdown, resource depletion, and construction waste have shifted architectural discourse away from abstract sustainability claims toward a more uncomfortable question: what are buildings actually made of, and at what cost? Within this context, upcycling emerges not as a trend or aesthetic preference, but as a critical rethinking of how architecture relates to time, value, and material life cycles. Unlike recycling, which often reduces materials to lower-grade forms, upcycling insists on transformation without loss—an architectural act that recognizes existing materials as repositories of energy, labor, and cultural memory. To upcycle is not simply to reuse; it is to reinterpret matter as a design intelligence already embedded in the built environment.

As cities accumulate layers of obsolete infrastructure, demolished buildings, and surplus industrial products, architects are increasingly confronted with a paradox: material abundance and material scarcity coexist. Upcycling operates precisely within this contradiction. It challenges the profession to move beyond extractive construction models and to see waste not as a problem to be hidden, but as a spatial resource waiting to be activated. This shift has profound implications for how architecture is conceived, detailed, taught, and valued.

From Linear Consumption to Circular Construction Logic

For decades, modern construction has followed a linear logic: extract, build, demolish, discard. This model prioritizes speed, efficiency, and short-term economic gain while externalizing environmental and social costs. Upcycling disrupts this logic by introducing circularity into architectural thinking, where materials are designed not for a single life but for continuous transformation. In practice, this means treating demolition sites as material archives, industrial byproducts as design inputs, and existing buildings as future quarries. Architectural value shifts from novelty to continuity, from pristine surfaces to material intelligence. This matters because buildings are no longer isolated objects; they are participants in long material narratives. By embracing circular construction, architects begin to design with awareness of what existed before and what will come after, embedding responsibility directly into form-making and detailing. The future of construction depends not on producing more materials, but on learning how to work creatively with what already exists.

Material Memory and the Aesthetics of Imperfection

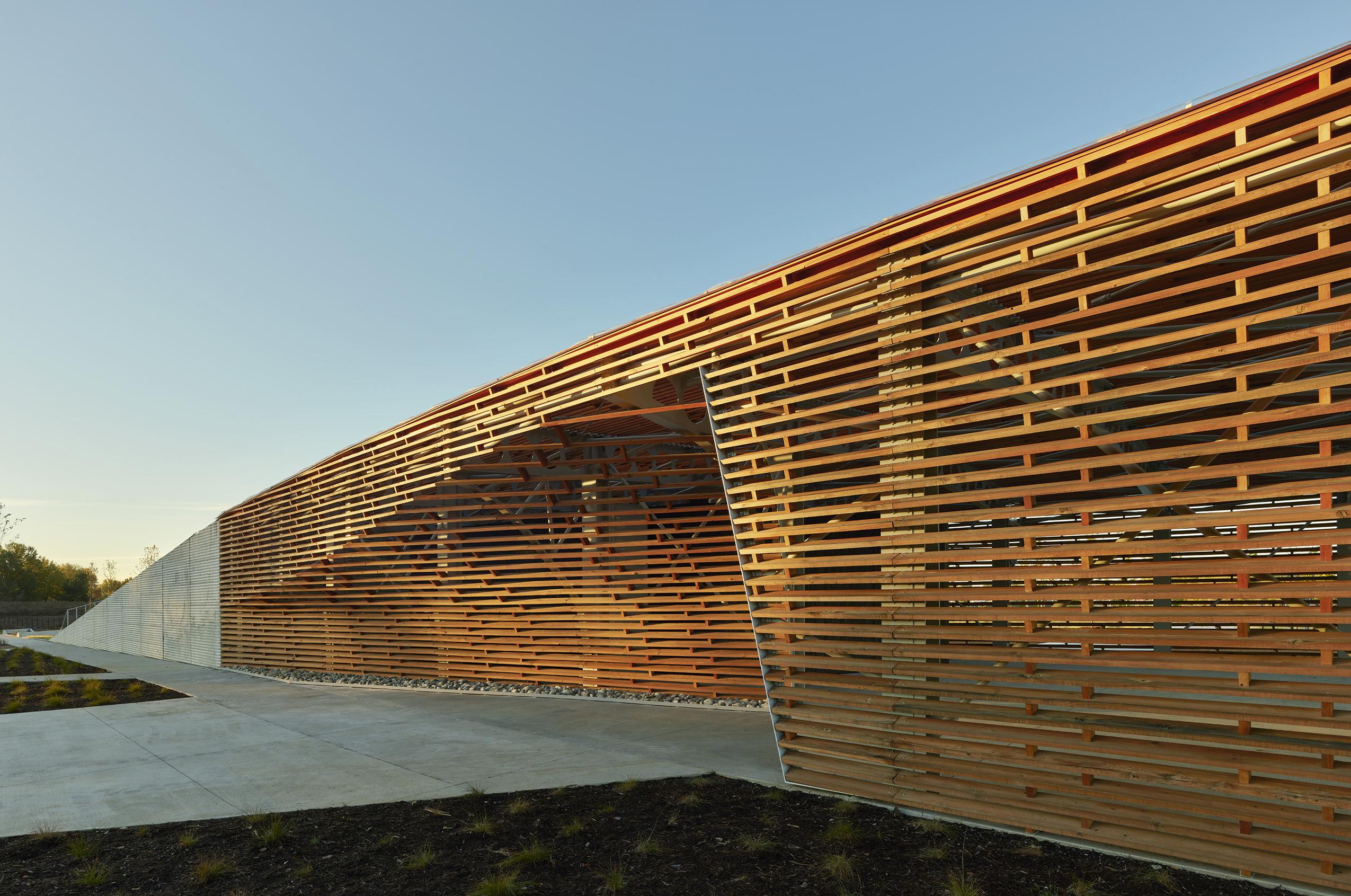

Upcycled materials carry visible traces of previous use—scratches, patina, irregularity, and wear. In conventional construction culture, such qualities are often seen as defects to be erased. Yet in architectural upcycling, these marks become sources of meaning. They tell stories of labor, time, and transformation that new materials cannot replicate. This shift reframes architectural aesthetics away from uniform perfection toward expressive material honesty. Exposed reclaimed timber, reused bricks with inconsistent coloration, or reassembled steel components introduce visual complexity and narrative depth into space. More importantly, they challenge the myth that quality architecture depends on flawless materials. In an age increasingly defined by environmental limits, imperfection becomes a form of ethical expression. Upcycled architecture communicates restraint, care, and awareness—values that resonate deeply within contemporary spatial culture. The result is not nostalgia, but a new architectural language grounded in continuity rather than consumption.

Design Innovation Driven by Material Constraints

Upcycling does not simplify architectural design; it complicates it in productive ways. Working with reclaimed or surplus materials demands adaptability, experimentation, and a departure from standardized construction systems. Architects must respond to irregular dimensions, limited quantities, and unknown performance histories. These constraints, rather than limiting creativity, often generate new forms of innovation. Structural systems evolve to accommodate non-uniform components, façades become modular and adaptable, and detailing becomes site-specific rather than generic. This material-driven design process repositions architecture as an act of problem-solving rooted in context rather than abstract formalism. It also rebalances authorship, allowing materials themselves to influence spatial outcomes. In this way, upcycling reintroduces uncertainty into design—a condition that modern construction has long tried to eliminate. Embracing this uncertainty fosters resilience, adaptability, and architectural intelligence that is better suited to an unpredictable future.

Upcycling as a Social and Economic Strategy

Beyond environmental impact, upcycling has significant social and economic implications for the construction industry. Reclaimed materials often come from local sources, reducing transportation emissions while supporting regional economies. Small-scale material recovery operations, salvage yards, and craft-based construction practices gain relevance within this ecosystem. Architecture becomes less dependent on global supply chains and more embedded within local material cultures. This shift also opens new possibilities for affordable construction, particularly in housing and community projects where cost constraints are acute. By redirecting surplus materials into meaningful architectural applications, upcycling can democratize access to quality spaces. It reframes sustainability not as a luxury, but as a practical response to inequality and resource imbalance. For architects, this means engaging more deeply with social realities, negotiating value beyond market-driven metrics, and designing systems that distribute material resources more equitably.

Rethinking Education and Professional Practice

If upcycling is to shape the future of construction, it must be integrated into architectural education and professional frameworks. Design studios traditionally begin with empty sites and unlimited material choices—an abstraction increasingly detached from real-world conditions. Incorporating material reuse into education forces students to confront constraints, ethical decision-making, and long-term thinking. It encourages research-driven design, hands-on experimentation, and interdisciplinary collaboration with engineers, material scientists, and builders. In practice, upcycling requires changes in building codes, procurement processes, and liability models, all of which currently favor standardized new materials. Architects advocating for upcycled construction must therefore operate not only as designers, but as negotiators within regulatory and economic systems. This expanded role signals a transformation in professional identity—one where architectural expertise includes material stewardship as a core competency.

Conclusion

Upcycling materials is not a marginal strategy for sustainable architecture; it is a fundamental reorientation of how construction relates to time, resources, and responsibility. As the environmental consequences of building become increasingly visible, architecture can no longer afford to operate as a discipline detached from material reality. Upcycling offers a way forward that is neither technocratic nor purely symbolic. It reconnects design with the physical and cultural lives of materials, insisting that architecture acknowledges what it consumes and what it leaves behind.

Looking ahead, the future of construction will be shaped less by new inventions than by new attitudes toward existing matter. Architects who embrace upcycling are not rejecting progress; they are redefining it. By designing with material continuity, imperfection, and constraint, architecture can evolve into a practice that is adaptive, ethical, and deeply embedded within its ecological and social contexts. In doing so, upcycling does more than reduce waste—it transforms the very foundations of architectural culture.

- eco-conscious building practices

- eco-friendly construction materials

- environmental sustainability in construction

- environmentally friendly construction

- future of sustainable construction

- green building design

- green construction techniques

- innovative architectural materials

- reclaimed materials in architecture

- recycled building products

- recycling in construction

- sustainable architecture trends

- sustainable building materials

- Sustainable Construction Innovations

- Sustainable Design Solutions

- upcycled architecture

- upcycled construction materials

- upcycled materials for buildings

- upcycling in architectural design

- upcycling in construction

Submit your architectural projects

Follow these steps for submission your project. Submission FormLatest Posts

9 Best Timber Frame Home Builders In PA For Sustainable Building And Design

Table of Contents Show Why timber frame construction makes sense in PennsylvaniaBudgeting...

Architecture Trends 2024: Top 10 Design Ideas Shaping Spaces

Architecture trends 2024 are redefining how we design and experience spaces. From...

Nature-Inspired Innovation: Biomimicry in Architecture

Biomimicry in architecture: a practical guide to nature-inspired design delivering 30–60% energy...

Green Architecture Explained: Designing for a Resilient Tomorrow

Green architecture explained through resilience: practical ways to cut carbon, improve health,...

Leave a comment