- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

Gaudí: Where Architecture Meets Science

Gaudí: Where Architecture Meets Science shows catenary arches, ruled surfaces, and biomimicry in action—physics-led design for form, light, and comfort.

Table of Contents Show

We talk about Gaudí with a kind of double-take: the fairy‑tale facades pull us in, then the engineering quietly blows our minds. Gaudí: Where Architecture Meets Science isn’t just a catchy line: it’s the way his work actually operates. He treated buildings like living systems, using geometry, physics, and material science to solve problems elegantly. If we want to design for beauty, performance, and longevity, we can learn a lot from how he fused intuition with rigorous experimentation.

The Mind Behind The Method

Gaudí’s studios were part workshop, part wind tunnel, part chapel. He wasn’t sketching fantasies and hoping they stood up: he was stress‑testing ideas with full‑bodied models, strings, sandbags, glass, and light. We see it in the crypt at Colònia Güell and, of course, in the Sagrada Família: a patient, iterative process where form emerges from forces.

He believed structure and ornament should be the same thing. That belief let him discard the heavy Gothic buttress and search for structural lines that carried loads cleanly, like the branching of trees or the sag of a chain. It’s why his buildings still feel futuristic. They’re not decorated containers: they’re resolved geometries that make decoration redundant.

Geometry As Structure, Not Ornament

Catenary Arches And Hanging Chain Models

Gaudí’s catenary arch is engineering humility turned into poetry. A hanging chain finds pure tension: flip the geometry and you get pure compression, exactly what masonry wants. In his workshop, he pinned strings and weighted them with shot bags, then photographed the inverted forms to “preview” the as‑built arches and vaults. The result is structure that works with gravity instead of fighting it. Think of the nave of the Sagrada Família: arches that don’t posture, they flow, because their math comes from physics, not whim.

Hyperboloids, Paraboloids, And Ruled Surfaces

Hyperboloids, paraboloids, and helicoids show up across Gaudí’s work because they’re ruled surfaces, made by moving a straight line. That’s the sly genius: complex curvature built from simple craft. The light wells in Casa Milà and the lanterns at Sagrada Família use hyperboloids to channel light and air while creating stiffness with minimal material. Ruled geometry gave stonemasons, bricklayers, and carpenters a clear way to build precision curves without CNC, just lines, templates, and patience.

Load Paths, Thin Shells, And Stability

When load paths are clean, everything else simplifies. Gaudí thickened where compression gathered and thinned where the structure could relax, anticipating thin‑shell thinking decades before it went mainstream. Vaults act like suspended membranes turned upside down: facades become stiff diaphragms: columns shift and tilt to keep resultant forces inside their cores. The outcome? Stability with less mass, better spans, and fewer hidden crutches. It’s structural art because efficiency and beauty end up being the same choice.

Nature As Blueprint: Biomimicry And Material Science

Branching Columns And Fractal Logic

Walk the Sagrada Família and you’re under a stone forest. Columns split into branches, diameters taper, and angles adjust so axial loads stay axial. The branching follows a kind of fractal logic: repeat a simple rule at different scales and you get rich complexity that’s still legible. This isn’t decoration: it’s a load‑bearing algorithm written in stone.

Ceramics, Trencadís, And Surface Performance

The colorful trencadís mosaics at Park Güell do more than charm tourists. Glazed ceramic sheds water, resists UV, and tolerates complex curvature with tiny pieces, which minimizes cracking and maintenance. The irregular tesserae also diffuse glare and add micro‑texture for slip resistance. Surface as performance layer, Gaudí had that baked in long before “building envelope” became a buzzword.

Stone, Brick, And Stereotomy

Gaudí’s stereotomy, the art of cutting stone for 3D assemblies, turned quarry blocks into precision components. Where stone was heavy, brick took over for lighter shells, often laid in thin layers with mortar to create strong, economical vaults. Material wasn’t a style choice: it was a system choice, tuned to compression, abrasion, moisture, and time.

Light, Color, And Environmental Physics

Daylighting And Chromatic Adaptation

Those stained‑glass gradients inside the basilica aren’t random. Gaudí balanced sky luminance, solar angles, and interior reflectance so the nave reads bright without glare. Warm and cool glass tones work with our eyes’ chromatic adaptation: as outdoor light shifts, the interior maintains a calm, even mood. Tessellated hyperboloids near clerestories bounce daylight deeper, turning structure into a giant light machine.

Ventilation, Thermodynamics, And Comfort

Before HVAC, Gaudí leaned on physics. Stack effect in vertical shafts, cross‑flow through courtyards, and pressure differentials shaped by rooftop forms keep air moving. Ceramic and stone add thermal mass to flatten temperature swings, while shading from overhangs and deep reveals cuts solar gain. Casa Milà’s undulating facade isn’t just iconic: it’s a wind‑tuned diffuser for Barcelona’s Mediterranean climate.

Acoustics In Sacred Space

In sacred spaces, clarity matters more than loudness. Gaudí used vault geometry, ribbing, and porous surfaces to scatter echoes while preserving speech and choral warmth. The varied curvatures act as broadband diffusers, avoiding hot spots and dead zones. It’s sound engineering literally carved into the ceiling.

Analog Computation And Prototyping

Scale Models As Experiments

We’d call them prototypes: Gaudí called them work. Large models let him tweak curvature, jointing, and light at 1:10 or 1:25, then feed changes back into craft details. Failure wasn’t a setback, it was data.

Inverted Photogrammetry To Draw The Plans

Those hanging models weren’t just demonstrations. By photographing them and inverting the images, Gaudí captured accurate geometries for masonry courses and profiles. It’s analog computation: gravity solves the equations, the camera records the answer, and builders get a clear roadmap.

From Gaudí To Parametric Design: Lasting Influence

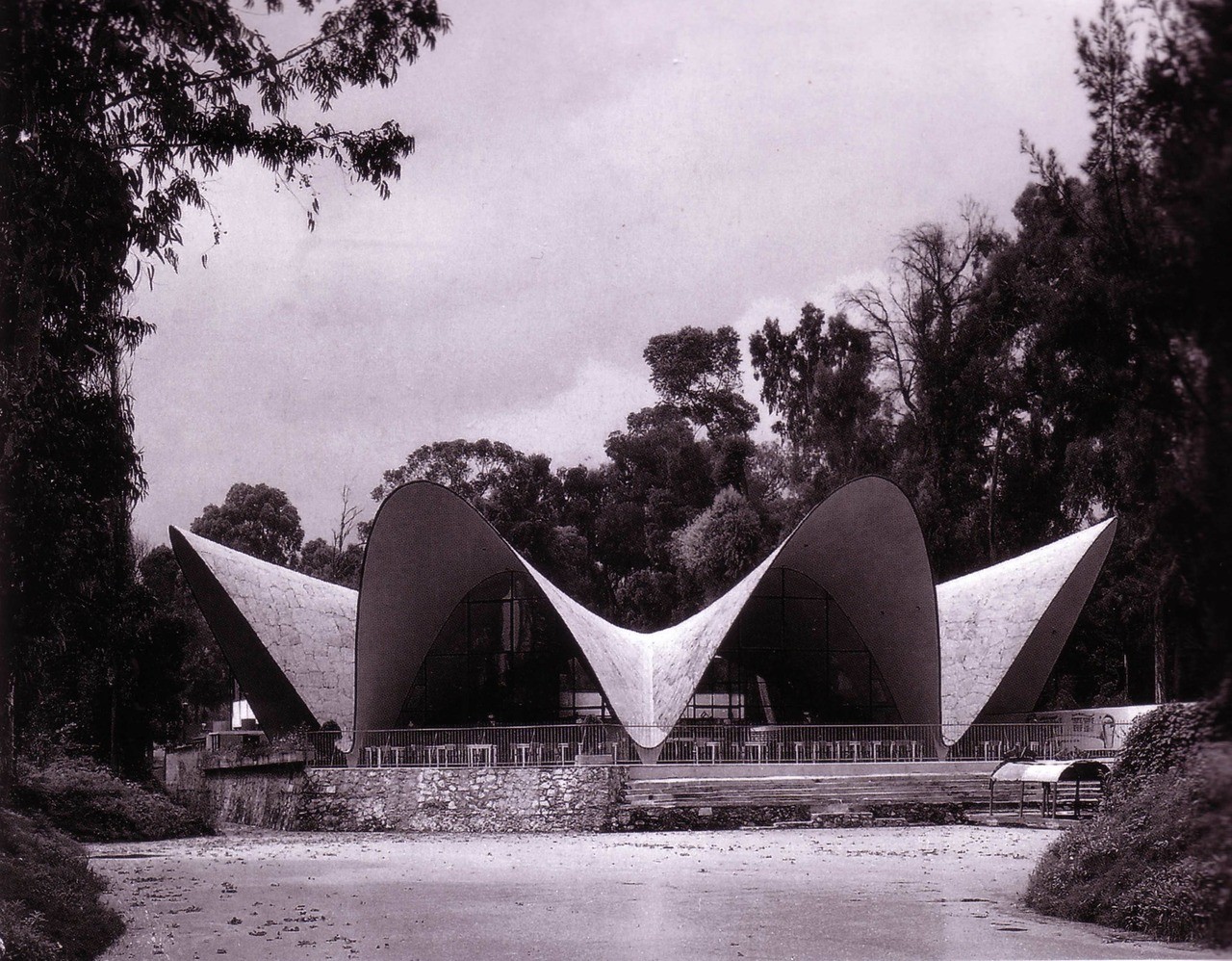

Structural Art From Candela To Contemporary

Félix Candela’s thin‑shell hypars, Eladio Dieste’s brick curves, and Frei Otto’s tensile roofs continue the same physics‑first lineage. They prove that when we honor load paths and material behavior, elegance arrives with efficiency.

Digital Tools Echoing Gaudí’s Logics

Today, Grasshopper, Rhino, and structural solvers like Karamba or SOFiSTiK let us iterate Gaudí’s logics at speed: ruled surfaces from straight generatrices, branching columns from constraint sets, daylight and CFD loops for feedback. The tech is newer: the questions are the same, what form does the force want?

Conclusion

Gaudí: Where Architecture Meets Science isn’t nostalgia, it’s a working method. If we let physics sketch with us, choose materials for what they do, and prototype until the form behaves, we get buildings that feel inevitable. And when structure carries both loads and meaning, we don’t need to add beauty at the end. It’s already there, doing the work.

- Architectural Innovation

- architecture and science company

- architecture and science integration

- architecture inspired by Gaudí

- architecture meets science

- architecture science collaboration

- creative architectural solutions

- cutting-edge architectural design

- Futuristic architecture design

- Gaudí architecture

- Gaudí design principles

- Gaudí inspired buildings

- innovative architectural designs

- integrating science in architecture

- modern architectural innovation

- science architecture firm

- science-based architecture

- science-driven design

- scientific architectural solutions

- urban design inspired by Gaudí

Submit your architectural projects

Follow these steps for submission your project. Submission FormLatest Posts

Top 10 Most Inspiring Women in Architecture

Explore the remarkable achievements of women in architecture who transformed the profession...

Acropolis of Athens: Architecture as a Political and Cultural Statement

From the Parthenon to the Erechtheion, the Acropolis of Athens stands as...

How to Understand Rental Appraisals: A Full Guide

Rental appraisals are essential for setting competitive rent prices and maximizing investment...

10 Things You Need To Do To Create a Successful Architectural Portfolio

Discover 10 essential steps to create a successful architecture portfolio. From cover...

Leave a comment