- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

- Home

- Articles

- Architectural Portfolio

- Architectral Presentation

- Inspirational Stories

- Architecture News

- Visualization

- BIM Industry

- Facade Design

- Parametric Design

- Career

- Landscape Architecture

- Construction

- Artificial Intelligence

- Sketching

- Design Softwares

- Diagrams

- Writing

- Architectural Tips

- Sustainability

- Courses

- Concept

- Technology

- History & Heritage

- Future of Architecture

- Guides & How-To

- Art & Culture

- Projects

- Interior Design

- Competitions

- Jobs

- Store

- Tools

- More

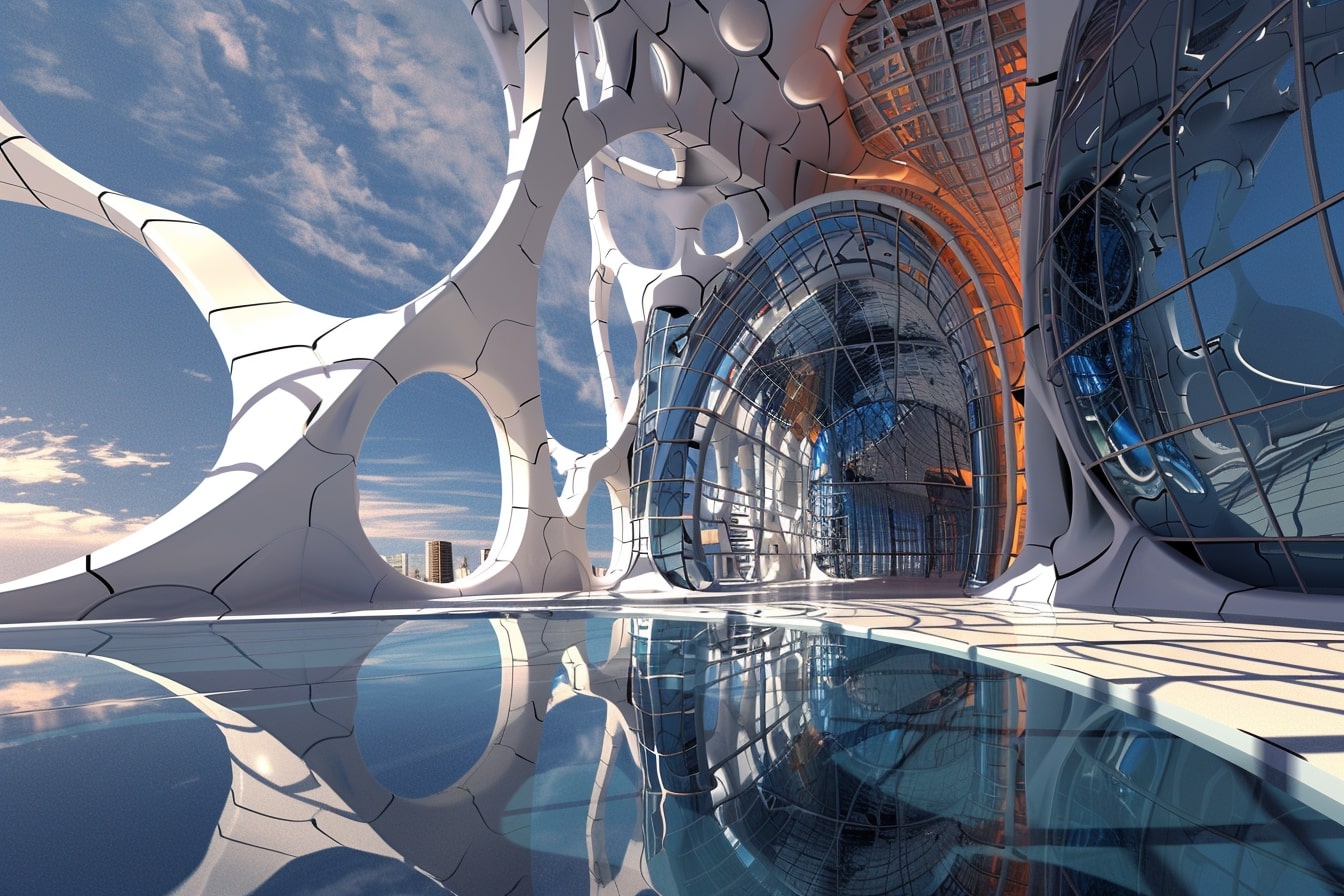

Form Finding in Architecture: Exploring Innovative Designs and Sustainable Solutions

Explore how form finding in architecture merges creativity with physics, shaping efficient, sustainable, and visually striking designs. From historical techniques to modern computational tools, this method unlocks innovative possibilities, inspired by natural forces and materials, while addressing challenges in execution and functionality.

Table of Contents Show

Architecture isn’t just about creating buildings; it’s about shaping spaces that inspire and connect us. One of the most fascinating processes in this art is form finding—a method where design emerges through exploration rather than strict preplanning. It’s where creativity meets physics, allowing structures to take on forms that are both functional and breathtaking.

We’ve seen form finding revolutionize how architects approach design, from iconic bridges to organic, flowing buildings. By letting materials, forces, and geometry guide the process, we uncover solutions that are not only efficient but also deeply rooted in nature’s logic. This approach challenges us to think beyond traditional methods and embrace innovation in every curve and contour.

Understanding Form Finding In Architecture

Form finding in architecture relies on exploring natural behaviors of materials and forces to shape designs, rather than imposing predetermined shapes. This process connects structural efficiency with aesthetic innovation, producing forms that harmonize with their environment.

Architects use computational tools, physical models, and performance simulations to guide form finding. Examples include parametric software like Grasshopper or real-world experiments with tensile membranes. These methods enable iterative adjustments that refine the relationship between structure, materials, and external forces.

Key elements influencing form finding include gravity, tension, and compression. For instance, Antoni Gaudí’s hanging chain models for designing curved arches and Frei Otto’s experiments with soap films exemplify how forces drive design. These principles result in minimal yet functional structures.

By prioritizing this integrative approach, architects address environmental concerns and maximize material efficiency, aligning modern designs with sustainable practices.

Historical Context Of Form Finding

Form finding in architecture has deep historical roots, evolving from rudimentary exploration of materials and forces to sophisticated methodologies in modern design. This approach reflects humanity’s pursuit of harmony between structure, aesthetics, and environmental forces.

Evolution Of Techniques

Techniques for form finding began with empirical methods in ancient civilizations. Builders experimented with natural materials like stone and wood to achieve stable, functional structures. Roman architects mastered arches and vaults using intuitive understanding of compression forces, exemplified by structures like the Colosseum and aqueducts.

The 19th century saw analytical advances through structural engineering. Engineers like Thomas Telford utilized precise calculations for bridge designs, incorporating iron in new ways. By the mid-20th century, modernist experimentation emerged, driven by scientific principles and computational tools. Frei Otto introduced physical simulation methods, like soap films and stretched membranes, to model natural efficiencies. These developments laid the groundwork for increasingly integrated and adaptive techniques.

Influential Architects And Projects

Several architects have defined form finding through groundbreaking projects. Antoni Gaudí used hanging chain models to design the Sagrada Família, showcasing gravity’s role in shaping arched structures. Frei Otto’s lightweight tensile designs, such as the Munich Olympic Stadium (1972), highlighted the potential of membrane structures.

In recent decades, architects like Zaha Hadid and Santiago Calatrava expanded form finding through computational technologies. Calatrava’s Milwaukee Art Museum illustrates biomimetic influences, while Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Center demonstrates fluid geometries engineered with computational precision. These projects showcase form finding’s enduring relevance in contemporary architecture.

Techniques In Form Finding

Form finding techniques in architecture blend traditional methods with modern tools to achieve innovative designs. These approaches leverage computational technologies and physical experiments to explore dynamic and efficient structural forms.

Computational Methods

Computational methods utilize advanced software to simulate and optimize forms based on mathematical algorithms and environmental factors. Parametric design tools, like Grasshopper and Rhinoceros, allow us to manipulate geometry interactively, responding to project constraints such as load distribution or material properties.

Finite element analysis (FEA) further enhances precision by modeling physical stress and deformation. Projects like the Eden Project in the UK demonstrate how computational algorithms optimize structural efficiency by simulating environmental loads on the hexagonal geodesic domes. These methods reduce material waste, align designs with natural forces, and enable architects to create highly adaptable forms.

Physical Modeling Approaches

Physical modeling approaches involve hands-on experimentation, offering tangible insights into material behavior. Architects use tension-based models, such as hanging chains or fabric stretched over frameworks, to explore structural principles. These experiments provide intuitive solutions grounded in natural physics.

Frei Otto’s soap film experiments exemplify the efficiency of physical modeling, showcasing minimal surface forms under tension. Similarly, Antoni Gaudí’s hanging chain models created inverted catenary curves for the Sagrada Família, which informed the building’s groundbreaking structural design. These techniques reinforce how real-world modeling remains integral in developing innovative architectural forms.

Applications Of Form Finding In Modern Architecture

Form finding has become a cornerstone of modern architectural practice, offering solutions that combine structural integrity with avant-garde aesthetics. By leveraging advanced tools and techniques, architects create designs that are both efficient and visually striking.

Structural Efficiency

Form finding enhances structural performance by aligning designs with natural forces. This approach minimizes material use, optimizes weight distribution, and reduces energy consumption. Examples include Frei Otto’s tensile membrane structures, like the Munich Olympic Stadium, which achieve strength with minimal material input. Similarly, the Eden Project utilizes geodesic domes to balance structural stability with lightweight construction. Digital tools such as Grasshopper allow architects to model stress and load accurately, helping refine structural elements through computational simulations.

Aesthetic Innovations

Form finding expands design possibilities, producing flowing, organic shapes that challenge traditional aesthetics. Projects like Zaha Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Center demonstrate how parametric tools can shape fluid, futuristic facades. Architects merge functionality with artistic expression, creating iconic landmarks that harmonize with their surroundings. Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família and Santiago Calatrava’s Milwaukee Art Museum illustrate how historical methods and contemporary technologies converge to craft visually dynamic spaces.

Challenges And Limitations

Form finding in architecture, while innovative, faces several challenges that impact its application. These limitations often stem from technological, functional, and practical constraints.

Technological Constraints

The reliance on computational tools introduces challenges related to software limitations and accessibility. Advanced programs like Rhinoceros and Grasshopper demand high computational power, specialized knowledge, and expensive licenses, making them less accessible for small-scale projects or emerging firms. For instance, inaccurate simulations due to processing limitations can lead to structural inefficiencies. Moreover, integrating data from environmental or material performance simulations often requires additional expertise and cross-disciplinary coordination, which can complicate workflows.

Additionally, the gap between digital modeling and real-world execution poses challenges. Translating complex geometries from parametric designs into physical structures demands precision, often requiring cutting-edge manufacturing techniques like 3D printing or custom prefabrication. These methods, however, come with higher costs and extended timelines, creating barriers for widespread adoption.

Balancing Function And Form

Achieving harmony between aesthetics and functionality frequently presents a key challenge. While form finding prioritizes innovative, organic designs, ensuring that these forms meet practical requirements like structural stability, usability, and environmental considerations is essential. For example, creating lightweight tensile structures that remain durable under extreme weather conditions can push material limits and increase engineering complexity.

Conflicts between design aspirations and project budgets also arise, especially when unconventional forms demand additional resources, materials, or specialized labor. Balancing client expectations and technical constraints often requires compromises that can dilute the creative potential of form finding. Lastly, addressing building codes or regulations while pursuing experimental forms adds another layer of complexity, further constraining design freedom.

Future Of Form Finding In Architecture

The future of form finding lies at the intersection of technological innovation and sustainable design. New advancements reshape how we conceptualize and create structures, with a focus on efficiency and environmental responsibility.

Emerging Technologies

Emerging technologies redefine form finding. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning enable architects to analyze complex patterns, optimize forms, and predict performance outcomes. For example, generative design algorithms suggest multiple design possibilities based on predefined parameters, significantly reducing time spent in the early stages.

Additive manufacturing, such as 3D printing, allows the direct translation of computational models into physical prototypes. Large-scale 3D printing creates intricate forms with minimal material waste, exemplified by structures like the TECLA bio-printed house. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) tools enhance spatial understanding, enabling architects to refine designs interactively during the form finding process.

Innovations in materials science, including self-healing concrete and carbon-fiber composites, expand the scope of feasible designs. These materials align with form finding principles by combining reduced weight with increased strength, optimizing both aesthetics and performance.

Sustainability Considerations

Sustainability drives the evolution of form finding. Architects focus on aligning designs with natural systems to minimize environmental impact. Lightweight structures inspired by biology, such as shells and webs, reduce material consumption and energy use. Notable examples include Shigeru Ban’s paper tube buildings, which utilize sustainable materials.

Parametric tools integrate environmental data, allowing for real-time simulations of lighting, wind, and thermal performance. These capabilities ensure energy-efficient designs, as seen in projects like the Al Bahar Towers, which feature responsive façades that adapt to sunlight.

Recycling and upcycling materials gain importance in form finding, promoting circular construction practices. Designs that incorporate materials such as reclaimed wood or recycled steel directly support sustainability goals. Additionally, green building certifications, like LEED, incentivize integrating eco-friendly strategies into form finding initiatives.

Conclusion

Form finding in architecture bridges the gap between structural efficiency and aesthetic innovation. It empowers architects to create designs shaped by natural forces, material behavior, and advanced computational tools, resulting in efficient, sustainable, and visually striking structures. Through historical evolution and modern advancements, form finding continues to revolutionize architectural practice. This integrative approach offers endless possibilities while addressing environmental challenges and pushing the boundaries of design.

- advanced architectural techniques

- architectural design technology

- architectural form exploration

- architecture design and sustainability.

- Architecture Innovation

- contemporary architecture solutions

- cutting-edge architecture design

- eco-friendly architecture solutions

- environmentally friendly architecture

- form and function architecture

- form finding in architecture

- green architecture methods

- Innovative Architectural Solutions

- innovative architecture designs

- innovative structure design

- Modern Architectural Designs

- sustainability in architecture

- sustainable architectural solutions

- sustainable building design

- sustainable design architecture

Submit your architectural projects

Follow these steps for submission your project. Submission FormLatest Posts

9 Best Timber Frame Home Builders In PA For Sustainable Building And Design

Table of Contents Show Why timber frame construction makes sense in PennsylvaniaBudgeting...

How Upcycling Materials Is Redefining the Future of Architectural Construction

Upcycling materials is reshaping how architecture understands value, time, and responsibility. Rather...

Architecture Trends 2024: Top 10 Design Ideas Shaping Spaces

Architecture trends 2024 are redefining how we design and experience spaces. From...

Nature-Inspired Innovation: Biomimicry in Architecture

Biomimicry in architecture: a practical guide to nature-inspired design delivering 30–60% energy...

Leave a comment